Articles Sawbridgeworth People

George Ottea, butler at Terlings Park

Theo van de Bilt has been researching people of colour living in the Sawbridgeworth area in the past and he found George Ottea who worked as a butler at Terlings Park in Gilston. He was working there in 1891 according to the census. There are fascinating stories of how he got there, his previous employment in London and how he met his wife. He was highly thought of by his employers and is buried in Gilston churchyard.

Morghi George Ottea and his family

Theo van de Bilt

For a while in the summer of 2020 Black Lives Matter dominated the headlines. As a result, I started to investigate the presence of people of colour in our area and how they left their mark. Nothing much came up, but one interesting story that I was pointed towards was about George Ottea and his family.

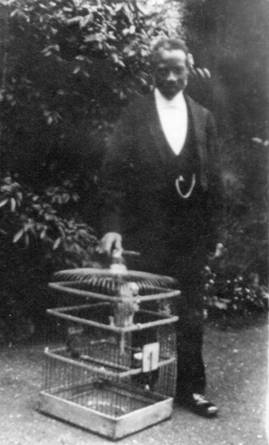

Morghi George Ottea, 1851-1926, was a black man who served as a butler at the residence of Reginald Eden Johnston, a one-time governor of the Bank of England who lived at Terlings Park House in Gilston. Where George came from is shrouded in mystery. There are two, slightly conflicting, stories (see below). Above, you see a picture of Ottea. I have no idea where his name Morghi (or Morghite) came from. For the sake of simplicity we will from now on refer to our main subject as George (photograph supplied by Veronica Johnston).

George’s origins are indeed unclear. His birthplace, as given in census records from 1871 to 1911, does vary: Africa; Gambia River; West Coast of Africa (British subject); Africa (resident) [with ‘British Africa’ added by the enumerator]. From the ages given on these and other forms circa 1851 seems a fair estimate for the year of George’s birth. As for further background, there are basically two stories. The first one comes from Johnners, Barry Johnston’s biography of his father, Brian Johnston, the cricket commentator. Brian Johnston was a grandson of the aforementioned Reginald Johnston. Brian (born 1912) often spent time at his grandad’s Terlings Park residence. According to family legend, our George was found in a burnt-out West African village by the crew of a British navy ship. This story was related to Barry by his uncle, Brian’s brother, Christopher (90 years old at the time); they were sons of Charles Evelyn Johnston, Reginald’s eldest son.

Another source was the postcard photograph shown at the beginning of this story. It was sent by Winifred M. Cuming to her brother Edward Hamilton Johnston (Reginald’s third son, known as Hamil) in 1928, and inscribed ‘A remembrance of past Christmases!’. An additional note was added later by Iris Johnston, Hamil’s widow. It read: ‘Ottea the African man servant at Terlings, rescued from a slave dhow as a boy’. Both ‘stories’ may have an element of truth but should also be taken with a grain of salt, having come to us decades after the death of our subject. The essential part of the story is of course that George was a black African coming from enslaved people.

Around 1851 Royal Navy ships did indeed patrol the Atlantic. Britain had at that point abolished slavery but Spain, Portugal and other nations had not. It then became the task of the ‘West Africa Squadron’ to intercept slave ships and ‘free their cargo’. Further research revealed that any one of eight vessels might have been the one that could have picked up young George: HMS Actaeon, Hyacinth, Iphigenia, Maeander, Owen Glendower, Pelorus, Queen Charlotte or Wanderer. The logbooks of these ships are kept at the National Archives. The National Archives have been closed, however, for most of the past year, so it would have been impossible to go there. Apart from that, what would have been the likelihood of the incident actually being mentioned?

Iris wrote about slave dhows. Dhows are two-masted Arab sailing vessels with triangular sails common in the Red Sea and the coastal waters of East Africa, but occasionally also off West Africa. Arab slave traders did use those vessels and were also active in the Gambia around 1850. More than that can’t really be said.

Somehow though, George ended up in London. The how when and where of that will probably always be shrouded in mystery. The first record of his existence that we have found dates from the 1871 census, when George, 19 years old, was employed as a footman at the London home of Charles Calvert Eden’s family, 73 Onslow Square, Chelsea. They also had property in Somerset, The Grange at Kingston St. Mary, near Taunton, where we will find him later on. On 9 September 1875, at St Margaret’s Church in Westminster, George married Emma Saunders, daughter of a London master tailor, Weston Saunders (their marriage certificate is below). George gave his father’s name as George Ottea, occupation unknown. Their witnesses were William and Sarah Read, who may have been friends. In the 1871 census a Sarah Read, aged 26, was the cook for the Edens in Onslow Square; and in the 1881 census a William Read was living in the same dwelling as Emma’s father and his family. In 1877 George and Emma’s daughter Edith Emma was born in London; a second daughter Anna (1879) and their son Denney George (1884) were born in Somerset. At the time of the 1881 census, George was still working in London for the Eden family, who had moved to Montagu Street, Marylebone. Emma, however, with Edith and Anna, was living in Kingston St Mary, close to the Eden Somerset property.

Below: the Ottea Marriage certificate

Above: the interior of St. Margaret’s Church Westminster

A few years later, George must have left the Edens’ employ. An article in the Taunton Courier of 11 May 1887 mentions him as the new landlord of the ‘Westgate Inn’, Shuttern. Five months later, on 5 October according to the same paper, George is in court and described as ‘a coloured man charged with furiously driving and thereby endangering the lives of passengers’. A Mr. Waldegrave told the court how George drove past him on Tone Bridge, how he warned him and told him that people could be hurt. ‘Several other people told him to be more careful’. As Ottea drove past him, so Waldegrave said, the horse was going at 15 miles an hour. Ottea ended up being fined 2s 6d plus costs. Two months later, on 7 December, George’s licence as landlord was transferred to a Mr. Holt. Am I alone in thinking there was a bit of victimisation going on there?

Whatever was the case, the 1891 census records George as a butler at Terlings Park in Gilston and employed by Mr. Reginald Eden Johnston. Emma and the children were living at 50 Hare Street, Great Parndon. The Eden and Johnston families were connected by Reginald’s marriage in 1875 to Rose Alice Eyres, whose first cousin was Charles Calvert Eden. Charles’s daughter Evelyn, aged 11, was one of Alice’s bridesmaids. Reginald’s middle name came from an earlier source.

To the left, Reginald Eden Johnston; to the right Terlings park in 1962.

The Johnston family made their fortune in coffee and banking. Between 1840 and 1880, their company, Edward Johnston & Sons, had extensive financial interests in Brazil. Based in Rio de Janeiro, Reginald’s father, Edward Johnston, had gone there at the age of 17 to work for a trading firm. He married Harriet Mary Moke, daughter of a pioneering Flemish coffee-planter, and in 1842 set up his own coffee-exporting company. The family returned to England in 1845, and he set up an office in Liverpool (the other end of the shipping route), then moved to London in 1862. Reginald and three of his brothers joined the family firm and were also involved in banking. By 1870, Edward Johnston & Co was the second largest exporter of Brazilian coffee. Reginald Johnston most probably bought Terlings Park in 1887 from the Duke Hill family. Between 1893 and 1911 Johnston was respectively director, deputy governor and governor of the Bank of England. Johnston and his wife had seven children, so Terlings Park house must have been a busy place.

Not much is truly known of George’s life with the Johnstons .Barry Johnston’s biography of his father Brian, tells us how he was being waited on at table by Ottea wearing immaculate white gloves’. Brian also related how one day someone informed the local otter hunt and told them there was an ‘otter’ up at the big house. The hunt duly turned up at Terlings and were rather taken aback when Ottea answered the door and asked whether he could help them” The joke here is that the name Ottea was pronounced by many as ‘Otter’!

In 1899, George and Emma were guests at the wedding in Taunton of Violet Eden to Captain Arthur Street of the West India Regiment. The Otteas’ wedding present was two silver pepper pots. Two years later, George and Emma, plus son Denney and daughter Anna, were recorded as living together in Gilston. Daughter Anna’s profession was given as parlour maid (with the Johnstons?); son Denney, 16, was a carpenter. In 1908 daughter Anna died. She was buried in St. Mary’s churchyard, Gilston.

On the left Gilston Church; on the right George Ottea’s grave.

Sadly, little more detail of George and Emma’s life in Gilston has emerged. George may have carried on serving the Johnstons until Reginald’s death in 1922. Reginald clearly was quite appreciative of George; his employer left him £300 in his will. That sum could then have been used to finance building the Bungalow at Pye Corner Gilston, where they lived. Morghi George Ottea himself passed away on 8 December 1926. His age is then given as 75.He is buried next to his daughter in St. Mary’s churchyard. George died a relatively wealthy man, leaving his widow Emma and daughter Edith effects worth £843. By then Terlings Park had been sold to the Bowlby family, who, until 1948, rented it out to various occupants. After that, Terlings Park House became the headquarters of the Harlow Development Corporation and from 1968 was used by the post office. In the 1970s, a fire destroyed the roof and the building was declared unsafe. In 1982, it was bought by pharma giant Merck to be used as a research establishment. In 2015, Terlings Park became a housing estate.

What then happened to the Ottea family? Son Denney served from 1905 until 1922 in the Navy, and had married Florence Maud Nial in 1916. The couple then had two sons, Lionel and George. Upon leaving the Navy Denney worked as a builder’s foreman. Like his dad, he was well respected. During the Second World War, he served in the High Wych Platoon of the Home Guard. It is said he built his own house, the Bungalow at Pye Corner, mentioned above. According to a later occupant, this was originally a wooden structure and built in the 1920s. So it is likely Denney in fact built it for his parents. In 1942, Denney’s youngest son, George, married Edna May Willett in Bedford. The local paper there mentioned ‘a colourful wedding’, a choice of words that would probably not be chosen nowadays! Young George was a leading aircraft-man in the RAF at that point. When one year later mother Emma (Butler George’s widow) died at Western House Ware, Denney was mentioned on the probate form. Denney’s sister Edith, meanwhile, had not married. In 1911 she worked as a dressmaker at Mount Vernon Hospital in St. Pancras, London. In 1958 Edith, too died, at Western House in Ware. Her father Denney had by then passed away. He died on 4 November 1954. Denney’s widow, Florence, continued to live in the Bungalow in Gilston, which her husband had helped build. Some locals still remember her. Florence passed away on 26 April 1975.

The High Wych and Gilston Home Guard Platoon; Denney Ottea is fourth from the left on the second row. Photo supplied by Jill Clark.

Young George stayed on in the RAF after the Second World War. He went to Canada, trained as an officeer and learned to fly. Back in the UK he was based at both Abingdon and Cramwell but also spent a few years in Singapore. The latter years of his airforce career he spent in Farnham after which, at age 48 he became a Midland bank manager in Sheffield. He passed way there in 1976; his wife Edna died in 1993. The older son, Lionel seems to have been a “complicated man” He worked as a builder and surveyor and was an active member of the Harlow Automobile Club. His first marriage, to a lady called Vera ended in divorce. In 1978 in Harlow he married Joanna Michalska who was of Polish origin. For a while, the couple then lived near Ringwood in the New Forest. After getting separated from Joanna he then met up with Myrtle who was described to me as Lionel’s “childhood sweetheart” They lived in Kirby Kane in Norfolk. His death was registered in Great Yarmouth in 2003. Lionel did not have children. As for young George, he had two daughters from his marriage to Edna May Willett, Carole and Rachael. Carole, had a son and a daughter and six grandchildren. Her sister also had a son and a daughter and four grandchildren. Carole has helped with this article and provided some photographs.

The photograph above on the left shows the wedding of George Ottea and Edna Willett. Mrs. Ottea is seated next to the groom. Denney Ottea stands at the back. The picture on the right shows George and Edna with baby daughter Rachael and her sister Carole in front of the bungalow in Gilston.

Thus ends the story of what must have been one of the first people of colour in our area. George Ottea’s presence amongst us, a black man in Gilston, must have been unusual, to say the least. Yes, one could say that employing black servants was occasionally done for ‘decorative reasons’. But there is no doubt that George Ottea was all the better for having worked at Terlings Park House, and that he was much appreciated. He obviously liked the Johnston children and they liked and remembered him. Still, it is a pity so little is known of him. Visiting his grave and that of his daughter at Gilston churchyard last year it was sad to find it in such a bad state of repair. Could it possibly be restored? It would be nice. Carole Cridland, butler George’s great granddaughter for one, would like to come over to Gilston with her son and daughter at some point and see what can be done.

Sources for this story were, and help came from: Audrey Collins, Jill Clark. Yolande Clarke, Carole Gridland, Colin Jackson, Roger Multon, John Oliver, www.ancestry.co.uk, The National Archives, Alistair Robinson’s History of Terlings Park, The Bedfordshire Times, The Taunton Courier, Barry Johnston, author of Johnners, the biography of his father, Brian Johnston. Special thanks go to Veronica Johnston for her persistent help and encouragement throughout the long gestation period of this article.

Theo van de Bilt 6 September 2021